|

ELECTRONIC AGE AUGUST 18, 1970

Mastering ‘Wool-fighting’ by Electronic Methods

"Knock over truck shog allows lower position of knock over during first course after rib transfer, to prevent tucking: also to allow a large slack course for running on and rib transfer purposes."

That is the sort of language Ron Martin, founder and managing director of Industrial Control Systems (1969) Ltd., has not only to understand, but for which he has to build electronic control systems.

It's a knitting machine—not the sort of granny-replacement over which your wife may slave, but a huge, complex monster which turns out six fully-fashioned garments at once. The Martin-designed controller accepts up to 120 channels of information, is all solid-state, and is so successful that the maker of the complete machine. S. A. Monk, of Nottingham; is all set for a world-wide export boom.

Before designing electronic control systems for any industry, the jargon and inbred expertise of the trade must be assimilated. Martin's experience in the knitting, metal finishing and treatment trades is, he believes, virtually unrivalled, but he is still eager to learn more occult arts.

Virgin Territory

The next virgin territory for sophisticated control systems will be, he thinks, the carpet manufacturing business, which may benefit from the experience in problem-solving acquired in the knitting world.

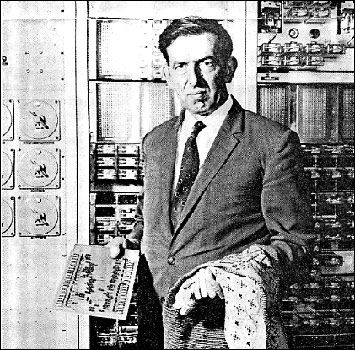

Ron Martin with examples of knitwear produced by machinery automated by ICS.

Martin told Electronic Age that the most surprising facet of this area was the lack of interest by many electronic experts in what he chose to describe as "partial automation". There were, he thought, many engineers and designers prepared to supply very advanced control systems, utilising the latest integrated circuitry, computer programmes and other exotic features. But the only "asset" these very sophisticated machines had in common was their vast expense.

They would, of course, probably do the job very well, but the step from virtually no automation at all to this very advanced stage was often too big for owners of existing machinery to take.

A sensible programme of "partial automation" such at that practised by Martin and his staff could, in many cases, be shown to benefit the workforce, helping them to achieve higher output and, in many cases, enabling other jobs further down the production line to expand to absorb workers which automation had replaced.

Martin‘s policy, in other words, is to aim for the middle ground of industrial control systems, which quite often do not interest bigger companies geared to large-scale problem-solving. This field is obviously very satisfying both in achievement and economic terms.

Simplification Needed

Many machines are apparently virtually unchanged inventions of the industrial revolution, and still work well. The level of many advances since the original concept has, he maintains, stopped at simple limit and proximity switches, counters and timers. The leap forward from there to completely-automatic, tape-controlled systems was too much for many operators.

Concentrating an improvements in time-scale of operations which could he measured in tenths of a second rather than nanoseconds. Marlin has proved that there is a very large market for his wares. And he is not alone. MinTech has, he insists, recognised that some entrepreneurs need help in this area, and has sponsored what he called “low-cost symposia”.

At a Birmingham session of that type, Martin was, he admitted, very impressed by the number and sincerity of the businessmen who enquired of him or his colleagues about a problem which boiled down to “How can I make these do this simply?”

This is why Martin does not subscribe to the accepted line on the failure of the machine-tool industry to really take-of in Britain. He is sure that, before the exotic world of numerical control can really get to grips with modern industrial problems, owners of existing machines will have to be introduced gently to the possibilities of electronics in simple stages.

A system such at his, which will automate partially four capstan lathes so that one operator can look after all four without undue strain, is the next logical step.

Impressive Start

Martin started ICS in 1964 in an old manor house at Grafton Regis, just outside Northampton. It is famous because of its links with Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV, but this fact had no appreciable impact on the early days of ICS, which, in Martin's words, "was and still is concerned with mechanical problems or 'iron-fighting' by electronic means"

Grafton Regis, in fact, was abandoned later in the same year, when the initial business in automating metal finishing plant grew too big for it to hold. The first few contracts were impressive enough for a much more established company. Rolls-Royce was the recipient of one of the biggest plating plants ever built in this country containing automated systems designed and installed by ICS.

That success was followed by some very important contracts for both Ford and General Motors in Australia. The plants which Martin automated while living in Australia for the duration and, incidentally, being sorely tempted to make his home there, were carrying-out such tasks as plating hub-caps and bumpers for cars.

Apart from the obvious desirability of relieving men from what can be a very unpleasant job in plating shops, the ICS automation system is also capable of delivering much better accuracies of control over most parameters.

Voltage smoothing, current control, timing of dips, movement and many other variables can be much more accurately monitored and controlled with a tireless electronic system than when left to human frailties relying on temperature, time of day, eating habits and many other physiological or psychological factors.

And, because working in a plating shop is not the most sought-after position in any factory, the quality of the labour which can be recruited may not always be of the highest standard. Low-grade labour can be a very expensive investment to any owner of an elaborate plating process plant which relies on minute control of dipping procedures for the delicate balance between profit and loss.

Drastic Saving

Marin calculates that replacing one man with one or more electronic control systems can save the employer somewhere between £1,500 and £2,000 per annum. And with investment grants and other government aids—if they continue to operate under the new administration—the time taken to amortise the cost of installing one of his systems could be reduced drastically.

From his early success Martin went into the esoteric world of knitting-machine control. Having already fathomed the depths of jargon which keep the "iron-fighting" business going, he was faced with the task of learning the language of "wool-fighting".

From the example given at the beginning this article, he must have found it somewhat daunting. Bat he appeared to enjoy the task and gave Electronic Age many more examples of his acquired skill, which would be virtually impossible to reproduce without an involved and tiresome lexicon.

Problem-Solving Satisfaction

How did he first get the entrepreneurial bug? Martin refused to give any of the normal, banal reasons for wanting to be his own boss. He was not a tycoon type obsessed with power for power's sake. Nor did he particularly seek piles of money.

The reason for starting on his own was much more mundane than most people imagined - he wanted to have a go" at it himself, and not sublimate his needs through other people, either in a large or small organisation.

With a whole range of patents from telephones for coal-mines to automated train control. Martin would have made his mark in any organisation, and did so in the old GPO, the RAF on radar, rind with Plessey, that hot-bed of embryo entrepreneurial talent.

Among his best-remembered moments of glory while working for others was the occasion at an IRE symposium in 1960 when he culminated two years of intensive and fascinating work on thin films by delivering a path-breaking paper on the application of materials to electronics.

Now, he adds with n wry smile, one of the eldest of his seven children, 18-year-old Richard, is doing chemical engineering and "tries to tell his old dad all about thin films".

Martin is well aware of the alternative to running this comparatively small business. He has not only worked within large corporations as another employee but, so successful was the first two years in business, he was taken-over by giant GKN, who allowed him to carry on as a sort of divisional manager within the empire.

He has nothing but praise for GKN and its management team, but explains that the aim was to rationalise the empire in logical divisional structures, which meant lumping what he considered to be an alien operation in one division under his control.

They wanted to rationalise, I wanted to specialise," he explains succinctly. While within GKN his workforce rose to more than 100, and he was housed in a brand-new factory in Northampton. GKN also gave him the responsibility for Unimate, the industrial robot which has received so much publicity both here and in the States.

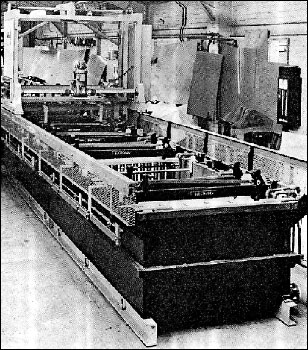

Metal-finishing plant controlled by ICS random-selection grear.

Marlin was responsible for "anglicising" Unimate, and while in the organisation got involved in many other fascinating and successful automation activities. In 1968 a management change at GKN led to the proposal to divisionalise on the lines which Martin thought unwise, so he took some of his men and some of his activities back out into the wide world to take his chances once more on his own.

Five Companions

With five companions and his wife Wendy, he started out once more on the lone trail, sure that was his métier. Now that the business is once more off the ground with more than 30 staff in 15,000 sq. ft. trying to make inroads into a plump forward order-book, he still insists that his greatest satisfaction is derived from the implied flattery of the calls he gets from ex-colleagues in larger organisations who want to join him.

ICS is now doubling its turnover each year, and of the last turnover figure which he was prepared to reveal, £110,000, about half is obtained from production equipment business. There are, in fact, three companies in his empire now—the other two are concerned with components and production equipment solely, as opposed to the original activity which concentrated on automation problems. Perhaps the most interesting new product in Martin's diversification activities is the logic lamp—if only because it is being produced by ICS on machines controlled by one of the machine-tool control systems. This means that the company can get not only the edge economically on any potential competition in this field, but the machines can act as realistic test-beds for any developments in control techniques.

Fellow workers are, after all, always the most demanding of critics. But the logic lamps themselves are claimed to be important for their potential as indicators capable of being connected directly into any circuit, producing three volts or more without the need for a separate driver circuit.

Electronics, of course, has its own jargon which can be off-putting to outsiders. Take the other new products which ICS is marketing—diode burn-in equipment and transistor burn-in rack, or even diode reverse bias burn-in equipment type 2. Of course, all readers of this magazine will know immediately exactly what these marvellous machines are designed to do.

|